Ask how the novel is coming along and I will tell you, “See my Substack.”

That’s misleading. Here I mostly post research notes on the periphery and not progress reports. But for once, here’s a progress report, or a reason for my lack of progress: I’m currently revising Chapter 18 of 30, but I have had to go back and deal with a particular out-of-place artifact in Chapter 14.

In Chapter 14, I introduce another monk, not an Ancient School Buddhist monk like Todor and Li Ban, but a Franciscan monk, Brother John, a plausible fiction. Before Marco Polo’s adventures, Dominican and Franciscan monks traveled through Central Asia and Mongolia. Like his fellow 13th century Franciscans William of Rubruck and John of Plano Carpini (Giovanni da Pian del Carpine), Brother John meets Christians of the Eastern Church, tries (and mostly fails) to convert others, participates in intellectual jousts with other holy men, and collects intelligence on the Mongol invaders. In addition, Brother John has the task of assisting Lazar in delivering his treasured message to Europe.

In Chapter 14, Lazar’s progress has been halted. In fact, he’s going the wrong direction, heading east to Mongolia and not west to Europe. Like Todor and Li Ban, and a congress of holy men, John arrives to aid Lazar in his quest to deliver the message. To this end, Brother John provides Lazar with two tools: a magnetic compass to help him with direction, a south-pointing-spoon; and what Brother John calls “seeing stones” that will allow Lazar to see better at a distance. By the 13th century magnetic compasses were in general use, especially with those in contact with Chinese civilizations. But lenses that have some telescopic powers were centuries away.

In previous chapters I dabble with the timeline of invention. My tinkers are developing hand cannons and fire lances, a plausible 13th Century development. But I must reconcile or at least cover up the facility of the seeing stones.

As I’m writing an historical adventure, my fictions might not agree with the facts, but must not diverge too much from fact. I’m not writing an alternate history, a counter-factual. I want every detail if not to lead to the world we live in but to at least not be a cause of interruption. Not to say counter-factuals don’t make for good reading(cf. Stephen Fry’s Making History and Star Trek’s “City on the Edge of Tomorrow.”)

It’s all fiction of course, but I want my historical adventure to maintain some consistency, obey internal rules, or at least some of them. Example: Superman can fly but that’s only because earth is relatively low gravity compared to Krypton. Superman fans leave aside that Clark Kent, having matured on a high gravity planet, should probably be a much squatter person.

That aside, would my seeing stones be possible?

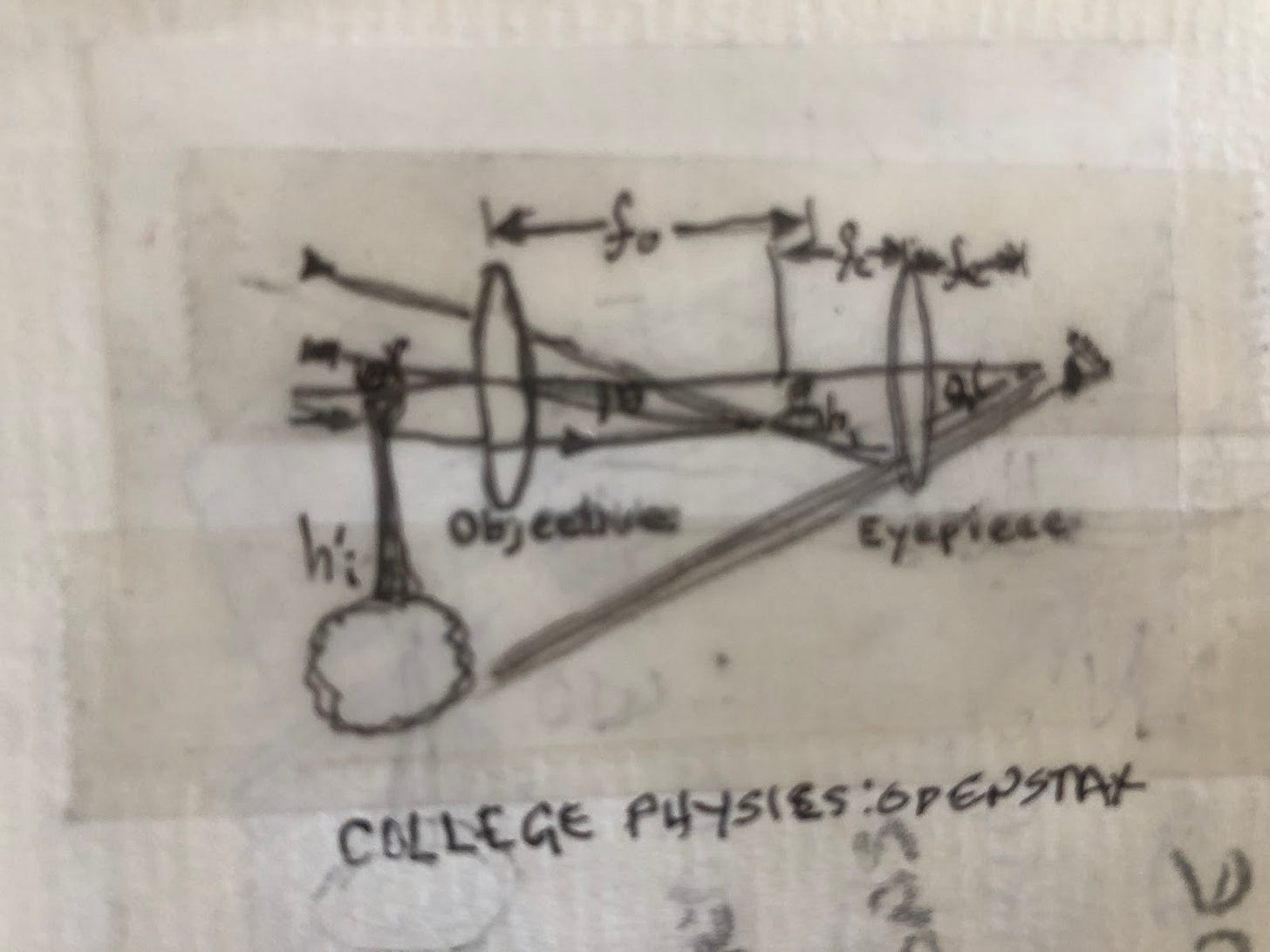

Central Asian Al Hazen (c. 965 – c. 1040) made great strides in the study of optics, and the Franciscan monks Robert Grosseteste (1175-1253) Roger Bacon (1219/20-1292) furthered that knowledge for Europeans. Telescopes though weren’t invented until more than three hundred years later. The first patents for a telescope were filed in 1608. Galileo made his own telescope in 1609 and wrote about his findings in Starry Messenger, for which he would have been burned if he had not recanted its findings. But Galileo’s telescope was a combination of convex and concave lenses. Concave lenses weren’t in use until the mid-15th century.

I tried to imagine other possibilities, to fit the fiction to the facts, including the possibility of molding concave lenses.

So, check, convex lenses were very popular to be used displaying relics. Convex lenses were also used to improve reading for the literate population of Europe, that is, the clergy. Some of the first lens grinders were monastic orders. Also, check. Perhaps Brother John gave the stones to Lazar because Franciscans abhorred possessions, or because they have not yet been approved of by the pope.

In Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose, set in Italy in 1327. The character William uses spectacles, which were said to be used as an object of “Witchcraft and diabolical speculation.”

Spectacles, though came after our protagonist, since they needed even finer grinding and the ability to match the dioptic powers of lenses that came later than monocular devices.

Assigning an exact date is clearly impossible, but the development of the optical effect was made in various monasteries rather soon after the first crusade, in the first half of the twelfth century requirement of such crystal plates for reliquaries the skilled grinding of rock-crystal lenses. It’s plausible Brother John’s has given Lazar two glass baubles, convex lenses common at the time. Their chief purpose was to magnify holy relics, which became quite common after the first crusaders ventures to the holy lands. As the saying goes, if all the relics brought back were real, John the Baptist would have had 12 hands and six heads.

It was certain, though, that a convex lens with 4x power had been developed by 1235. But the monks were only capable of making convex curved surfaces, Lenses that magnified.

So, in trying to fit the fiction to the fact, I researched further and found that a correspondent of Galileo’s, Johannes Kepler, had followed Galileo’s telescope with his own telescope, one with two convex lenses.

After playing with lenses, I think I’ve found the solution to showing that two convex lenses, using proper focal lengths, can increase an object’s size and maintain acuity. Although as Al-Hazen did, Lazar saw the images as upside down.

If I’m not writing alternative history, I’ll have to deal with my discovery later in the narrative—to make a discovery that is not discovered.

Do the lenses survive their trip to Europe? I’m not sure.

But until then, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Fiction!”